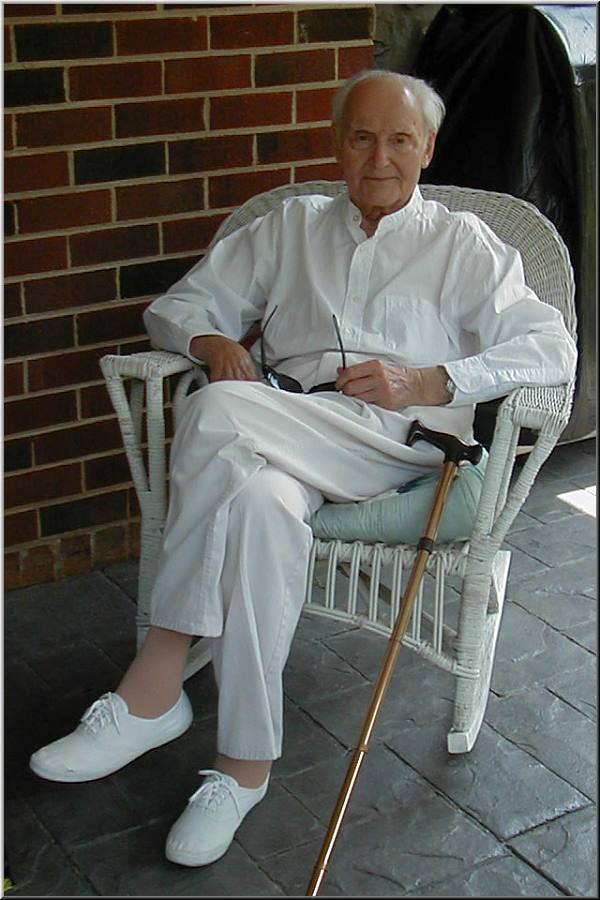

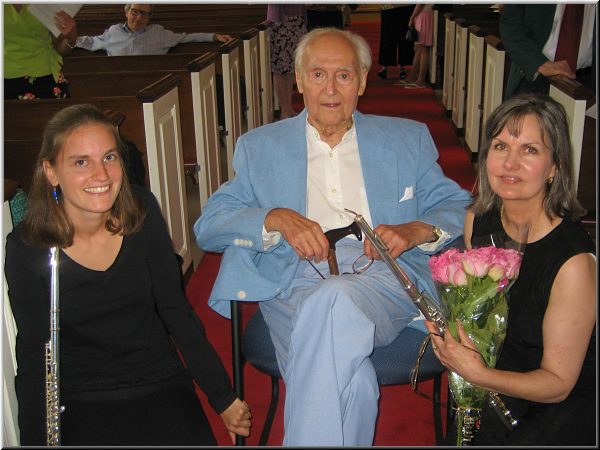

Salem (Viriginie, U.S.A.), mai 2007

(collection Deborah Kemper, flûtiste et professeur au Roanoke College de Salem) DR

|

|

| Dirigeant une répétition |

|

| Avec l'une de ses élèves, Emma Hileman |

|

| En concert, le 27 mai 2007 |

|

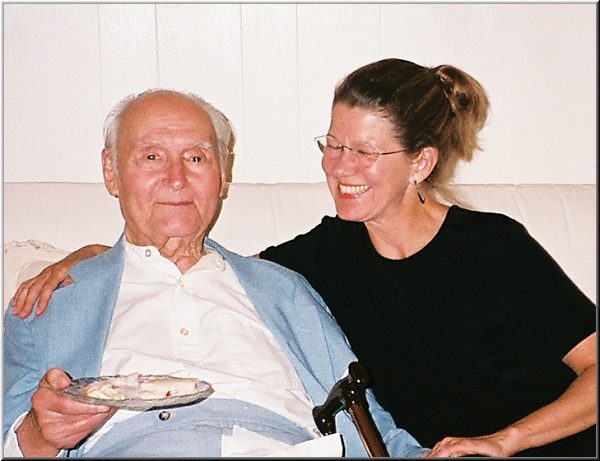

| Entouré de deux stagiaires, Anne Herby et Deborah Kemper (à droite) |

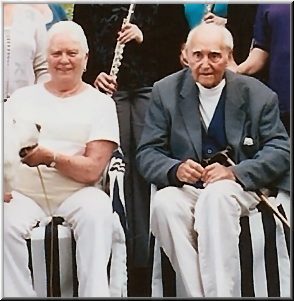

Masterclass de Montpelier (Vermont, U.S.A.), juillet 2007, les dernières photos...

(collection Laura Larson, flûtiste) DR

|

| Janet et Louis, 19 juillet |

|

| Leçon de flûte à Deborah Kemper avec Alison Cerutti au piano et Rebecca Collaros tournant les pages, 19 juillet. |

|

| Louis et Laura Larson, 21 juillet. |

Louis Moyse

Memories and Musings by Karen Kevra

For as long as I can remember, I have associated the name of Louis Moyse with the flute. As a 9-year-old beginner flutist, I accumulated volumes of Louis’s edited works, such as his ubiquitous 40 Little Pieces for Beginning Flutists and later the mainstay Flute Music by French Composers. By the time I became a teenager, it seemed that the majority of the music in my library had his name printed on it. Everywhere I turned I saw “Louis Moyse.” Who is this guy? I used to wonder.

I was soon to discover that Louis Moyse was more than a great pedagogue, prolific editor, composer of distinction, world-class flutist and pianist: he was also one of the warmest and most generous men on earth.

Twelve years ago, at a post concert reception at the home of Jim Lowe, Barr-Montpelier Times Argus arts editor, Jim insisted that I listen to a 1972 recording from the New England Bach Festival on which Louis was flutist in the “Süsser Trost” aria from Bach’s Cantata #151. I had never heard flute playing like this before. His playing combined the passion and depth of a great voice with a rich and haunting cello-like sound. I was completely under the spell of his playing and I knew that I needed to seek him out. Several months later the time came. With a mix of intense excitement and trepidation, I drove from Montpelier, over the Appalachian Gap, across Lake Champlain, to Westport, New York where Louis and his wife, Janet lived at the time. It was September 18, 1996.

For me it was a kind of flute pilgrimage. I was going to play for the most venerated living flute guru. I remember that first lesson vividly, from the magnificent twisted locust trees that flanked the Moyse’s driveway, to my initial sighting of Janet in her spectacular garden, to my first unforgettable glimpse of a smiling Louis as he released the final chord of a Beethoven piano sonata and our eyes met for the first time. In that moment I knew my life was about to change.

I played a Bach sonata and a French virtuoso piece for him that day and when I finished, he asked me, “Why did you come here?” My answer was as spontaneous and as natural as the question was fair. “I came here because I want to understand music.” […]

Louis was born before the automobile and experienced boyhood in a kind of rural innocence with his family in his native village of Saint Amour in eastern France. Paris in the 1920’s was his training ground and he had regular encounters with Fauré, Saint-Saëns, Stravinsky, Messiaen, Prokofiev and Martinu and even played piano duets with Duke Ellington during that time! In the 12 years that I knew him, Louis was quick to point out that “I am not of this time.” He had something of a distrust of the telephone and complete disdain for computers. His disdain for the modern age only made him more lovable.

Two years ago, in a coaching session I shared with my colleague and friend the pianist, Jeffrey Chappell, we played a Romance by Widor. When we finished, Louis reminded us that the piece was written for Paul Taffanel, professor of flute at the Paris Conservatory when Louis was a boy. He described Taffanel’s “concert day routine” – slowly elaborating the details. He described how Taffanel would carefully clean and oil his flute, followed by a lengthy walk around Paris, a leisurely nap and a good meal. He said, “These people lived very differently than you do now. They took the time to live. They took the time to sleep. They took the time to talk. They took the time to eat. They took the time to love.” He told us that this is what we needed to bring to the music. And we knew how right he was.

In a letter dated March 13, 1997, Louis shared with me some of his unique philosophy of life and spirituality: “Without love life doesn’t make too much sense. . . I put ‘God’ into a modulation by Schubert, in the trees, in my love for my dear Janet, in a sunrise or sunset, in nature, in everything beautiful, in friendship.” […]

Over this past weekend, I spent hours listening to my recorded coaching sessions with Louis. The immediacy of his teaching, the vitality of his voice, and the richness of his laughter were such reassuring gifts. Louis was insistent and consistent. There he was – speaking to me again, asking me to “Give life to your sound. Give life to the phrase.” Many teachers will implore you to “sing” but Louis wanted more from his students and he got it. But we were the lucky recipients.

Thank-you, Louis for believing in me and for giving me one of the greatest gifts of my life: the understanding of music...

Retour à l'article principal