ALEXANDER TANSMAN

(1897-1986)

|

| Alexander Tansman in Vienna in 1926 ( photo by Herm. C. Kosel, Vienna ) We are grateful to Madame Mireille Tansman Zanuttini and Madame Marianne Tansman for permission to publish the photographs on this page. |

The course of Alexander Tansman's life almost matches the sequence of major historical events in the 20th century. It comprises four principal periods:

1897-1919 Childhood and adolescence in Poland

1919-1941 Youth and early career in the Paris of the inter-war years

1941-1946 Exile in America

1946-1986 Maturity and final years in France

Alexander Tansman was born on 12 June 1897 in Łódź, Poland, in the same city as his famous compatriot, the pianist Arthur Rubinstein. Since 1795 Poland had been divided between the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Russian Empire. Lódź was in the part dominated by Russia. Alexander's parents, Mosze Tansman (1868-1908) and Anna Gurwicz (1866-1935) were members of the Jewish upper middle class, a highly cultured group in which the French language was commonly spoken. They took pains with Alexander's education, providing him with the best teachers of the day as well as foreign governesses. He quickly learned to speak five languages (Polish, Russian, German, French and English)[1].

At a very early age, about four or five, he learned the piano. All the family were musical to a high degree. His aunt had been a pupil of Anton Rubinstein in St. Petersburg, a cousin was a pupil of Eugène Ysaÿe in Brussels and his sister studied with Arthur Schnabel in Berlin. The family home was often the scene of chamber music performances, and from a very early age Alexander was taken to concerts by his parents. At the age of six, after an Ysaÿe concert, Tansman decided he would be a musician. He began composing at the age of eight or nine. His first piano teachers were Wojciech Gawrónski (1868-1910)[2], who came specially from Warsaw to teach him and lodged in the Tansman home, Karol K. Lüdschg, of Czech origin, and the Hungarian pianist Sándor Vas. From 1902 to 1914 Tansman studied piano, harmony and counterpoint at the Łódź Conservatoire.

Tansman never formally studied orchestration. His apprenticeship came about in the Łódź Symphony Orchestra during the First World War he played the parts for the harp on the piano. In doing so, he learned about orchestral colour and mixed timbres.

In 1915 he left Lódź to study in Warsaw. Here he worked to develop his musical knowledge, studying counterpoint, form and composition with Piotr Rytel (1884-1970)[3]. At the same time, he studied at Warsaw University's Faculty of Law and Philosophy, gaining his doctorate in 1918. From 1917-18, although almost completely cut off from Western musical developments, he composed works employing polytonal harmony and exploring innovative resolutions beyond the limits of functional harmony.

In 1919 Tansman won the three first prizes (the Grand Prix and the next two prizes) in the first national award scheme for composers held in Poland, which was now once more independent. He had sent in three works, under three different names. The prize compositions were a Romance for violin and piano, and two piano pieces: Impression and the Prelude in B major. Tansman had just completed the three scores early that year[4]. His success in the competition prompted his decision to go to Paris.

Tansman obtained his passport from the newly installed Head of State in Poland, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the then President of the Council of Ministers. Paderewski was himself a pianist and a gifted composer. Later, in 1927, Paderewski went to the United States to be present when Tansman gave his American debut, playing his Second Concerto for piano and orchestra.

Arriving in Paris in late 1919, at the age of 22, Tansman worked for a while as a packer at La Villette. He then made use of his language skills to find work in a bank. His circumstances rapidly improved. Little more than six months later he was able to bring his sister to Paris, and in less than a year after arriving he arranged for his mother to come as well. Within a year, he was making a living from his music. At first his earnings came mainly from giving piano lessons, but he rapidly became a concert pianist, touring Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Holland and Belgium.

Tansman had a friend, a Polish architect called Stanislaw Landau, who introduced him to Georges Mouveaux, a stage designer at the Paris Opera. Georges Mouveaux held a dinner at his home to introduce the young composer to Maurice Ravel. In his turn, Ravel introduced Tansman to his publishers Demets and Max Eschig, and to performers of musical scores.

Ravel also took Tansman to meet Roland-Manuel, who had a reputation for his Monday gatherings. There Tansman came to know Milhaud, Honegger, Roussel, Florent Schmitt, Ibert, and other French composers. The lightness and spirituality of the French musical tradition was often to show through in his own compositions[5].

|

| Alexander Tansman at the home of Vladimir Golschmann and his wife in St. Louis (U.S.A.) in 1931, watching while Prokofiev tries out Tansman's Second Concerto on the piano. ( Photo: Ruth Cunliff Russel, St. Louis, U.S.A. ) |

Ravel also gave Tansman a letter of introduction to the conductor Vladimir Golschmann (1893-1972). At that time, Golschmann was directing his orchestra in avant-garde concerts in Paris, the renowned Golschmann Concerts. At these, Tansman attended the first performances of his own most recent symphonic scores, composed in Paris from 1920 onwards. His Impressions for orchestra were performed at the Salle Gaveau on 3 February 1921, and his Intermezzo sinfonico at the Salle des Agriculteurs on 21 December 1922. Later, on 5 May 1924 in Brussels, Golschmann conducted the world premiere of the Danse de la Sorcière [6]. To the end of his life, Golschmann would continue to be one of the most faithful interpreters of Tansman's music, both at the head of the St Louis Symphony Orchestra, which he conducted from 1931 to 1958, and later as conductor for the Denver Symphony Orchestra from 1964 to 1970[7].

Ravel also introduced Tansman to the singer Marya Freund[8]. On 2 February 1922 she performed the composer's Eight Japanese Melodies at the Vieux-Colombier theatre under the direction of André Caplet.

In 1922, Tansman was the author of the first article about Karol Szymanowski to appear in French, in the Revue Musicale of Henri Prunières. At concerts organized by the Revue Musicale he made the acquaintance of Bartók, Hindemith, Casella and Malipiero. The concerts took place either at the home of Prunières, or at the premises of the Revue in the Rue de Grenelle, or at the Vieux Colombier theatre.

Tansman often spoke about the atmosphere he experienced in the Paris of between the wars, when there were no hierarchical distinctions and composers would show one another their work. At the Paris salons, creative artists from different disciplines - musicians, writers and painters - were able to come together. On Sunday afternoons, Tansman frequented the salon of Madame Paul Clemenceau, who was Austrian by birth and was the sister-in-law of Georges Clemenceau. There too he met Albert Einstein, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Stefan Zweig, who gave him a letter of introduction to Richard Strauss. « On a Sunday evening », Tansman recalled, « we would go to the Godebskis, who were close friends of Ravel. There I met Gide, Manuel de Falla and Viňes »[9].

After hearing a performance conducted by Golschmann of a work composed by Tansman (probably the Intermezzo sinfonico), Serge Koussevitzky (1874-1951) began to take an interest in the Polish composer. Tansman dedicated to Koussevitzky the two symphonic scores he wrote in 1923, a Scherzo sinfonico and a Légende. Koussevitzky conducted them both at the Paris Opera, on 17 May 1923 and 8 May 1924, with the Koussevitzky Concert Orchestra, which he had formed from a select group of the leading musicians in the French capital.

On 13 November 1925 a symphonic work by Tansman was heard for the first time in the United States, when the Boston Symphony Orchestra, directed by Serge Koussevitzky, performed the Sinfonietta no. 1 for chamber orchestra (1924). A few days later, on 22 November, Willem Mengelberg conducted the New York Philharmonic Society Orchestra in the Danse de la Sorcière at New York's Carnegie Hall.

A few months later, on 12 June 1926, Tansman's First Concerto for piano and orchestra (1925) was performed at the Paris Opera by the Koussevitzky Concert Orchestra, conducted by Serge Koussevitzky. On 28 May in the following year, Koussevitzky led the world premiere of the Symphony no. 2 in A minor with the same orchestra in the same place.

In June 1926, during a SIMC concert in Zurich at which Grzegorz Fitelberg was conducting his Danse de la Sorcière, Tansman met the impresario Bernard Laberge, who was then working with Ravel and Bartók. This meeting led to Tansman's first United States tour, in the company of Ravel, from November 1927 to January 1928.

While Tansman was sailing for the New World, Koussevitzky was preparing to welcome him with the first American performance in Boston, on 17 November, of the Symphony no. 2 in A minor by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The high point of Tansman's American tour was the world premiere of the Second Concerto for piano and orchestra (1927), also in Boston, on 28 and 29 December 1927, with the same performers as the Symphony and with the composer himself at the piano. This concert was repeated in early January at Carnegie Hall in New York. The work was dedicated to Charlie Chaplin, who attended the premiere. Tansman was to remain on very friendly terms with Chaplin. Through his publisher, he often sent Chaplin his latest published scores.

During this tour, Tansman made friends with Gershwin and invited him to Paris. Gershwin came to the French capital a few months later, at the time when he was composing his symphonic poem An American in Paris. He worked with Tansman on orchestrating this composition, and the two friends went together to the Avenue de la Grande-Armée to listen to the car horns which Gershwin used to represent the urban cacophony of traffic noise in a big city.

Tansman was always ready to help his colleagues. He gave introductions to his publisher Max Eschig to Villa-Lobos, Varèse, Mihalovici and Szymanowski, and later did the same for other composers much younger than himself.

Like many composers in the 1920s, Tansman came under the influence of jazz, which had been discovered by the Europeans after the 1914-1918 war. His tours to America, followed by his enforced exile during the Second World War, brought him into contact with the greatest of the jazz musicians, such as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and, especially, Art Tatum. He was greatly impressed with the rapidity and alternating rhythms of Art Tatum's compositions[10].

1929 saw the publication of the first musicological studies of the work of Alexander Tansman. An article by Raymond Petit was published in the February issue of the Revue musicale. Alejo Carpentier contributed an article on « Alexandre Tansman y su obra luminosa » to the September issue of Social (volume 14, no. 9). In 1931, the American critic Irving Schwerke published the first monograph devoted to Tansman and his work [11].

In the early 1930s the title « School of Paris » was attached to a group of composers settled in the French capital, all friends with one another and all from central and eastern Europe. There was the Romanian Marcel Mihalovici, the Russian Alexander Tcherepnin, the Hungarian Tibor Harsányi, the Czech Bohuslav Martinu, the Swiss Conrad Beck and the Pole Alexander Tansman. All of them composed in their own style, bringing to the French musical tradition a greater formality and firmness, a rhythmic vigour supported by refined accentuation, the modulation of melodies from the different musical traditions represented in the group, and a more linear approach to composition, sometimes using techniques neglected since the Baroque era.

In everything he wrote, Tansman drew frequently on Polish sources[12], not only dance forms such as the mazurka, the oberek, the kujawiak and the polka, but also in his melodic line (with the Polish scale and its emphatic fourth degree) and especially in his harmonic writing[13].

In 1931 Tansman dedicated a composition to « Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth of Belgium ». This was his Symphony No. 3, Symphony Concertante, written for a quartet with piano and orchestra, a rare combination. The work was performed on 6 March 1932 at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, under the direction of the composer, with the Belgian Keyboard Quartet.

Tansman had the honour of playing in a duet with Queen Elizabeth, who was a violinist a

and had been a pupil of Eugen Ysaÿe. Later, in 1958, he dedicated his Suite baroque to her.

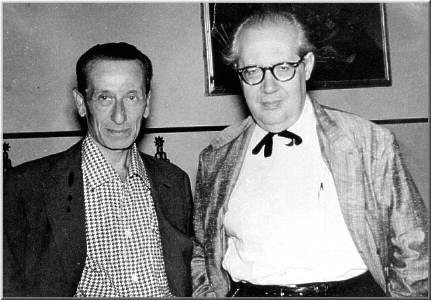

|

| Sergei Prokofiev and Alexander Tansman in St. Louis (U.S.A.), 1932. ( Photo Ruth Cunliff Russell, St-Louis, U.S.A. ) |

In 1932 he made his first tour of Poland. It was a great success, especially in Warsaw, where in September he gave the first performance of his Third Sonata for piano, completed in June of the same year.

On 6 October 1932 Arthur Toscanini, who did not attempt many contemporary works because of his blindness, conducted the New York Philharmonic Society in Tansman's Quatre Danses polonaises, having learned them by heart. This ground-breaking concert marked the beginning of a key chapter in Tansman's life: his voyage round the world. After a major tour of the United States, he went to Hawaii, Japan, China, the Philippines, Singapore, the Indonesian islands Java, Bali and Sumatra, Ceylon, India, Egypt, Italy and the Balearic islands. During this journey, he was received by Emperor Hirohito[14] of Japan. While staying in India, Tansman spent six days with Gandhi, at the latter's invitation. The tour lasted almost a year. Shortly before the composer's death, a film about it was shown at the Polish Institute in Paris and on Polish television. Tansman's impressions of the journey were transposed into a charming collection of piano pieces entitled Le Tour du monde en miniature (1933) which was performed by the BBC in London in 1934, with the composer himself at the piano.

Although he was known internationally as a Polish composer, in 1933 Tansman set to music a series of twelve Chants hébraïques, his first avowedly Jewish creation. A young woman singer he had known who came from Yemen, sang him some beautiful Jewish melodies which had been preserved in Yemen and which sprang from the purest Jewish tradition. It is said that they originated with the lost Twelfth Tribe. This composition was the beginning of a series of works in which the composer strove to bring out the specific yet universal characteristics of Judaism and its philosophical contribution to humanity[15]. In 1938 Tansman made use of these songs in his Rhapsodie hébraïque for small orchestra and piano. This work was performed in Paris in 1939 by the French National Radio Orchestra, conducted by Rhené-Baton.

It was around this time that Tansman started a new direction in his career by composing music for films. His debut came in 1932, when he joined forces with Julien Duvivier to compose the music for Poil de Carotte.

In the second half of the 1930s, one consequence of the political situation in central Europe was that Tansman's music was heard less and less often. His name was put on a blacklist of Polish musicians who were said to be producing « degenerate art » [Entartete Kunst], alongside the names of Arthur Rubinstein, Bronislaw Huberman, Pawel Kochanski, Arthur Rodzinski, Leopold Godowski and many others[16].

However, in 1936 Tansman made a second tour of Poland. Polish radio organized and broadcast a concert of his works, including the Concertino for piano and orchestra (1931) and the Deux Moments symphoniques (1932), which met with little reaction from the Warsaw critics. In much the same way, the Deux Pièces (1934), performed on 11 December 1936 during a concert by the Warsaw Philharmonic under the baton of the Luxembourg conductor Henri Pensis, were ignored. Increasingly outraged by the conduct of the Polish Government of the time, which was collaborating with Hitler's Germany, Tansman decided to renounce his Polish nationality. On 1 June 1938, he was granted French nationality under a decree signed by the President of the French Republic, Albert Lebrun. Alexander Tansman was to remain a French citizen, following the example of Igor Stravinsky two years earlier and presaging the same move by Bruno Walter a year later.

In spite of the difficult political situation, the list of Tansman's works lengthened to include many significant compositions such as the Quatuor à cordes no. 4 (1935), the ballets La Grande Ville and Bric à Brac (1935), the Fantaisie pour violoncelle et orchestre (1936), the Concerto for alto and orchestra (1936-1937), the Variations sur un thème of Frescobaldi (1937), the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra (1937), the Concerto for violin and orchestra (1937), the Sérénade no. 2 for string trio (1937), a second opera called La Toison d'Or (1938) on a libretto by Salvador de Madariaga, the Trio no. 2 for violin, cello and piano (1938), the Symphony No. 4 (1939) and the first two collections of Intermezzi for piano (1939).

The difficulties caused by the restrictions on democracy in Europe, and the looming menace of war, influenced the treatment of several works composed by Tansman during this period. Some of them, such as the Fantasy for cello and orchestra, or the Concerto for violin and orchestra, were first performed in their orchestral versions only after the Second World War. Others, such as the Fantasy for piano and orchestra, or the Symphony No. 4, which is among Tansman's most personal creations[17], have still to be performed, almost sixty years after they were composed. The opera La Toison d'Or was performed only in 1947, on French radio, in a version with two pianos produced by Bronislaw Horowicz.

On 7 December 1937, Alexander Tansman had married Colette Cras, a pianist of repute who was the daughter of the composer Admiral Jean Cras and herself an outstanding pianist. Two daughters, Mireille and Marianne, were born of the marriage. In August 1940, Tansman fled to Nice with his family to escape the threat posed by the enemy to the Jewish community in occupied France. He continued to compose tirelessly, especially for the piano[18]. In 1940 came the Rhapsodie polonaise for orchestra or piano, with the dedication « Homage to the defenders of Warsaw ». Owing to the strongly symbolic character of this work in the historical backdrop of war, not surprisingly, this was one of the two Tansman scores, with the Symphony No. 5 in D (1942), most frequently played by the major American symphony orchestras during the composer's years of exile[19]. During this dark and troubled time Tansman also composed his Fifth String Quartet, one of his most intensely dramatic compositions. It was performed in San Francisco on 3 August 1942 by the Budapest Quartet.

In 1941, with the support of a committee set up by Charlie Chaplin, Arturo Toscanini, Serge Koussevitzky, Eugene Ormandy and Jascha Heifetz, Alexander Tansman was able to leave France. As soon as he reached the United States, Tansman had the backing of Mrs. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge[20], who commissioned him to write a sonata for 5000 US dollars. On 30 October 1941, in the Coolidge Auditorium of the Library of Congress in Washington, Alexander Tansman performed his Fourth Sonata for piano for the first time. The same evening, he was awarded the Coolidge Medal, together with the composers Benjamin Britten and Randall Thompson (1899-1984).

|

| Igor Stravinsky and Alexander Tansman in Hollywood, 1945 ( photo X... ) |

Shortly afterwards, Tansman settled in Los Angeles, where he found many other European artists and intellectuals who had been forced into exile by the war, such as Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, Darius Milhaud, Thomas Mann and Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco. He became a firm friend of Igor Stravinsky and his wife Vera, meeting them almost daily. Tansman has spoken of the Hollywood of this period as a kind of « modern Weimar ». The American years were dominated by his composition of three symphonies: the Fifth in D; the Sixth In Memoriam (1944), dedicated to those who had fallen for France, comprising four movements, each with a different instrumentation[21], and which was performed in Paris after the Liberation by the choir and orchestra of French radio, directed by Roger Désormière; and finally, the Seventh « Lyrical » symphony, which was dedicated to Vera and Igor Stravinsky and was later performed under conductors such as Vladimir Golschmann, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Franz André, Eduard Flipse, Eugene Ormandy and André Cluytens.

Because of Hollywood's film industry Tansman was able to provide security for his family, while continuing to work at more serious compositions. He wrote a series of film scores around this time, including scores for Julien Divivier's Flesh and Fantasy in 1941 and Dudley Nichols' Sister Kenny in 1946. A plan to compose the score for Fritz Lang's film Scarlet Street was abandoned in 1945.

In 1944, the composer and conductor Nathaniel Shilkret invited a number of emigré composers to contribute to a group work entitled The Genesis Suite, which was planned as a musical accompaniment to a speech recording of the Bible. Shilkret asked each composer to write a short piece illustrating a chapter from Genesis. The chosen composers were Arnold Schoenberg, with his Prélude op. 44, Alexander Tansman, with Adam and Eve, Darius Milhaud, with Cain and Abel op. 241, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco with Noah's Ark, Ernst Toch with The Flood, and Igor Stravinsky with Babel. As the creator of the project, Nathaniel Shilkret kept for himself the episode of the Creation. It was intended that Bartók, Hindemith and Prokofiev would produce compositions for other chapters of Genesis, but this never happened. The work was performed in Los Angeles on 18 November 1945 under the direction of Werner Janssen. It could well be revived one day, either in the concert hall or as a recording.

Tansman returned to France in April 1946. Little by little, he regained his place in the country's musical life. Significantly, one of the very first works he composed on his return was called Ponctuation française, setting to music in a cycle of melodies some short writings by Charles Oulmont which has been composed in hiding during the Second World War. But it was mainly abroad, in Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland and Britain that Tansman's work was acclaimed afresh. He was by now in the prime of life, reaching the age of fifty in 1947, and there were many symphonic performances of his works in one country after another. The homage to his reputation began with a series of concerts in the Netherlands, performed by the country's leading orchestras (Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, the Hague Philharmonic Orchestra, the Utrecht Symphony Orchestra) under the direction of the composer, with Colette Cras[22] at the piano.

In 1948 Tansman published a major work on Stravinsky[23], the fruit of deep familiarity with the composer's work and regular meetings with him during the years of exile. He also composed Music for Orchestra (Symphony No. 8), which was performed by Rafaël Kubelik in 1949 at the XIIth International Bienniale of Contemporary Music in Venice. In 1950 it was directed by the same conductor with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, and by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra the following year.

The oratorio Isaiah the Prophet appeared in 1950. The composer had worked from several chapters of Isaiah's Old Testament prophecies. The selected chapter fragments are brought together within the general scheme of an oratorio. The composer's intention was to show the transition from suffering to joy via a prayer and a song of hope. Tansman composed this work both as a memorial to the six million Jews who had been exterminated during the Second World War, and as a salute to the new State of Israel. The work comprises seven parts, including a fugue for the orchestra alone and an interlude for wind instruments. This is the first of the three works[24] which, for Tansman, ranked highest among all his compositions and of which he was genuinely proud. It was performed on French radio in 1952 by the national choir and orchestra under the direction of the composer. Three years later it had its American premiere in Los Angeles under the direction of Franz Waxman, and a recording was conducted by Paul van Kempen.

In 1953, the year which saw the tragic death of his wife Colette, Tansman completed his opera Le Serment, from a libretto based on Balzac's « La Grande Bretêche ». This is the most frequently performed of his operas. It is a lyrical episode in two scenes, lasting about fifty-five minutes. André Cluytens directed the world premiere in a concert performance in 1954 on French radio. The first stage production was on 11 March 1955, at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels. The Italian premiere was directed by Bruno Maderna at Milan's R.A.I.

Tansman's Capriccio for orchestra, a very Stravinskyan work, was composed for the Louisville Orchestra, commissioned by the Ford Foundation and recorded immediately. His next composition was the Concerto for Orchestra, a major symphonic work which was to see many performances under the baton of many different conductors[25].

In 1958 Tansman completed his most important opera Sabbatai Zevi, a lyrical fresco in a prologue and four acts on a libretto by Nathan Bistritzky. The same year, from 14 to 31 July, he made his first visit to Israel.

|

| Alexander Tansman at his piano in Paris, in the 1960s. ( Photo Richard de Grab, Paris - New York ) |

In 1959 and 1960 he taught composition in Santiago de Compostela, and gave a lecture entitled « Some thoughts on tradition, substance and spirit in contemporary music ».

In the first half of the 1960s, Tansman composed major works in a variety of genres: ballet (Résurrection, 1962, on an argument of Pierre Médecin after Tolstoy), religious music (Psalms for tenor, mixed choir and orchestra, 1961), opera (Il usignolo de Boboli, 1963, on a plot of Mario Labroca); symphonic music (La Lutte de Jacob avec l'Ange, 1960, a symphonic movement inspired by Gauguin), Six Studies for orchestra, 1962; Six Mouvements for string orchestra, 1963, Concerto for cello and orchestra, 1963; instrumental music (Suite in modo polonico for guitar, 1962, Fantasy for violin and piano, 1963).

In 1967 Tansman was awarded the Hector Berlioz prize by S.A.C.E.M. (the Society of Music Authors, Composers and Publishers), and he made his first postwar visit to Poland.

Now began the composer's last creative period, no less productive than in the past, with Tansman still fully master of all his artistic resources. The period is dominated by a series of major symphonic works in which he deploys all his expressive gifts, with a perfect sense of alternating mood between liveliness and pensive calm. These works use a refined harmonic language which manages the effects of tensions and their resolutions in a rich virtuoso style of orchestration and a clear and effective formal construction. They include the Four Movements for orchestra of 1968, the Diptyque for chamber orchestra and the Hommage à Erasme de Rotterdam of 1969, the Stèle in memoriam Igor Stravinsky in 1972, the Ėlégie in memory of Darius Milhaud in 1975, the Sinfonietta no. 2 for chamber orchestra in 1978 and the Dix Commandements in 1979.

On 5 May 1977 Tansman was elected to Belgium's Royal Academy, in the Fine Arts class, to replace Dimitri Shostakovich who had died two years earlier.

The years 1977 to 1980 saw a marked resurgence of interest in Tansman's music in his native Poland. A Tansman festival was organized for his 80th birthday[26], and a second was held in Poznan on 17 February 1978 [27]. In 1979 Tansman made another visit to Poland, from 13 to 20 June. Then followed a major Tansman festival, from 26 September to 10 October 1980, featuring many compositions, among them some which were only seldom performed[28]. During Tansman's final years, the Polish authorities awarded him many distinctions: the medal of the Association of Polish Composers, the Order of Merit of the People's Republic of Poland, and the Order of Merit of Polish Culture.

In 1982 Tansman wrote his last concert score, his Hommage à Lech Walesa, a mazurka for guitar. To the end of his life, Tansman had a deep concern for the problems of the modern world. In these difficult years of Poland's history, he could not fail to express his admiration for the courage of the trade union leader who was to become Poland's Head of State only a few years later.

In 1986, the year of his death in Paris on 15 November, Tansman was awarded the title of Doctor Honoris Causa of the Lodz Academy of Music, and in September of the same year, France honoured him with the Order of Arts and Letters[29].

Gérald Hugon

Translation from the French : Patricia Wheeler

[1] Later in life, Tansman added Spanish and Italian to the languages he had learned in youth.

[2] Wojciech Gawrónski (1868-1910), a Polish pianist, composer and conductor, had studied composition at the Warsaw Institute of Music with Noskowski, and later studied in Berlin with Moritz Moszkowski. He may also have worked on orchestration with Brahms. As a pianist he made many tours in Poland and Russia, and was especially admired for his interpretations of Bach and Chopin. From 1902 he taught in Warsaw and at the Lodz school of music. His works comprise two operas, symphonic music, choral works, four string quartets, sonatas and pieces for string instruments and piano, as well as songs.

[3] Piotr Rytel (1884-1970), a Polish composer and music teacher, composed mainly operas, ballets and four symphonies. In addition to Tansman, his pupils included Tadeusz Baird (1928-1981), Andrzej Panufnik (1914-1991) and Wlodzimierz Kotónski (1925).

[4] This exploit was repeated forty years later, in 1959, when the young Krzysztof Penderecki, in similar circumstances, won the three first prizes in the competition organized by the Association of Polish Composers, sending in his Strophes for soprano, narrator and ten instruments, Ėmanations for two string orchestras and Psalms of David for mixed-voice choir, two pianos and percussion.

[5] A typical example of Tansman's French inspiration is the first "Pastoral" movement of the Third Sonatina for piano (1933).

[6] It was during this concert that Golschmann introduced Tansman to Pierre Monteux, who some years later conducted the Suite symphonique de la Nuit Kurde (1926), the Toccata (1929) and the Deux Moments Symphoniques (1932).

[7] Among the many Tansman scores conducted by Vladimir Golschmann, mention should be made of the Triptych for string orchestra (1930), the Concertino for piano and orchestra (1931), the Deux Moments Symphoniques (1932), dedicated to Vladimir Golschmann, the Deux Pièces for orchestra (1934), dedicated to Arthur Toscanini, the Adagio for string orchestra (1936), the two versions (for symphony orchestra and for string orchestra) of the Variations on a theme of Frescobaldi (1937), the orchestral versions of the Toccata and Fugue in D minor B.W.V. 538 of Johann Sebastian Bach (1937) and of the Two Chorals B.W.V. 705 and 599 (1939), the Rhapsodie polonaise (1940), the Symphony no. 5 (1943), the Serenade no. 3 (1943), the Divertimento for chamber orchestra (1944), the Symphony no. 7 (1944), the Suite dans le goût español (1949), the Ricercari (1949), the Sinfonia Piccola (1951-52), the Concerto for orchestra (1954), the Suite baroque (1958), and the Diptyque (1969). Those of the above works which were given world performances under Golschmann's direction are shown in bold.

[8] Marya Freund (1876-1966) had studied violin with Pablo de Sarasate before becoming a singer. She began her career in the opera theatre of her native Breslau (now Wroclaw). Schoenberg admired her musical talent and asked her to sing the part of Tove when his Gurrelieder were performed. Later, in Paris, she sang two other works of Schoenberg: the 15 Gedichte aus das Buch der Hängenden Garten von Stefan George op. 15 and the Pierrot lunaire.

[9] From a broadcast by Catherine Ravet and Alain Jomy, on France Musique (Radio France), 28 February 1985.

[10] The Tansman compositions in which the infuence of jazz shows through most clearly are the Sonatine for violin or flute and piano (1925), the ballet Lumières (1927), the Sonatine transatlantique for piano or orchestra (1930), the Symphony no. 3 « Concertante » (1931), No. 1 of the Tour du monde en miniature (1933), the ballets Bric à Brac and La Grande Ville (1935), the « Blues » no. 6 of the Huit Novelettes for piano (1936), Trois Préludes en forme de blues for piano (1937), Carnival Suite for orchestra or two pianos (1942), Ricercari for orchestra (1949), the ballet Resurrection (1962), and the « Tempo di blues » no. 2 from the Album d'Amis (1980).

[11] Irving Schwerke, Alexandre Tansman, Compositeur polonais, Paris 1931, Ėditions Max Eschig.

[12] « I can say this honestly. I have followed much the same route as Bartók or Falla, for example, inventing on themes from folklore. I have not used popular themes, but I have used the same sort of melodic line. This is because Polish folklore is very rich in both harmony and melody », in « Alexander Tansman: Œuvre et Témoignage, in Les Chemins de la Connaissance, broadcast no. 1: “La Pologne, Enfance et Vocation” by Marie-Hélène Pinel, broadcast on 8 March 1980 on France Culture (Radio France).

[13] So many of Tansman's compositions show a Polish influence that it would crowd the text to list them all. The most important ones are: Sinfonietta no. 1 (1924), String quartet no. 3 (1925), Symphony no. 2 in A minor (1926), Suite for two pianos and orchestra (1928), Suite-Divertissement for violin, alto, cello and piano (1929), Quatre Danses polonaises for orchestra or piano (1931), Deux Pièces for orchestra (1934), Fantaisie pour violoncelle et orchestre (1936), Sérénade no. 2 for violin, alto and cello (1937), Rhapsodie polonaise for orchestra or piano (1940), Tombeau de Chopin for orchestra or string quintet (1949), Ricercari for orchestra (1949), Suite légère for orchestra (1955), Concerto for clarinet and orchestra (1957), Musique à Six for clarinet, string quartet and piano (1977), Sinfonietta no. 2 (1978), and many piano works, including the Sonate no. 2 (1928) and the four collections of Mazurkas (1918-1928, 1932, 1941), as well as many of his guitar compositions; Mazurka (1925), Trois Pièces (1954), Suite in modo polonico (1962) and finally, the Hommage à Lech Walesa (1982).

[14] Interview on 10 August 1986 with Christine de Obaldia, broadcast on France Culture (Radio France), in "Mémoires du siècle", on 14 December 1986.

[15] This series of works includes the Chants hébraiques (1933), Deux Images de la Bible for orchestra (1935), the Rhapsodie hébraïque (1938), Adam et Eve no. 2 from « The Genesis », suite biblique for narrator and orchestra (1944), the Suite hébraïque for orchestra (1944), R'hitia Jewish Dance for piano (1944), the Prière hébraïque for tenor, mixed voice choir, piano or organ (1945), Kol-Nidrei for tenor, mixed voice choir and organ (1945), Ma Tovu - How Fair are thy tents for tenor or baritone, mixed voice choir and organ (1946), Le Cantique des Cantiques for chamber orchestra (1946), La Sulamite for chamber orchestra (1946), the oratorio Isaïe le Prophète (1950), the Quatre Prières pour choeur mixte sur des Psaumes de David (1951), Deux Pièces hébraïques for organ or piano (1954-55), the Album d'Israël for chamber orchestra (1958) or Visit to Israel for piano (1958), Prologue et Cantate for female choir and chamber orchestra (1957), the lyrical fresco in a prologue and four acts called Sabbatai Zevi, le Faux Messie (1957-58), the Psaumes for tenor, mixed voice choir and orchestra (1960-1961), Eli, Eli, Lamma Sabatchani in memorian d'Auschwitz for voice and piano (1966), the Apostrophe à Zion for choir and orchestra (1976-1977), and Les Dix Commandements for orchestra (1978-1979).

[16] See Janiusz Cegiella, Dziecko Szczescia Aleksandr Tansman I Jego Czasy, vol. 1, p. 348, Lodz, 1996, Wydawnictwo 86 Press.

[17] In fact the first world performance of the Symphony no. 4 took place only in June 1998, in the recording sessions organised by the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, directed by Israël Yinon for the firm of Koch-Schwann.

[18] In 1940 the composer completed the Valse-Impromptu, the 3rd and 4th collections of Intermezzi and the four collections of piano pieces for 4 hands entitled Les Jeunes au piano. Before he left Nice in 1941, Tansman had finished the Sonate for two pianos, the three pieces Mazurka, Canzone orientale and Moment musical, the three Ballades, the 3rd and 4th collections of Mazurkas, the Six Etudes de virtuosité and the Sonate no, 4.

[19] The Rhapsodie polonaise was performed in St. Louis on 11 and 12 November 1941 at the Opera House, Kiel Auditorium by the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, directed by Vladimir Golschmann. Other performances took place on 16 and 18 April 1942 with the Cleveland Orchestra directed by Arthur Rodzinski, on 25 October 1942 with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra directed by Dimitri Mitropoulos, on 3 January 1943 with the New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra directed by Dimitri Mitropoulos, on 31 January in Washington and 2 February 1943 with the Washington National Symphony Orchestra directed by the composer, and on 14 and 15 March 1943 with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra directed by Vladimir Golschmann.

[20] In 1925 Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge (1864-1953) had set up a foundation under her own name at the Library of Congress in Washington to enable the music department of the Library to organize festivals and concerts and to make grants of money and award prizes for any original composition performed in public at festivals or concerts held under the auspices of the Library. In 1932 she instituted the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Medal, which is awarded every year to one or more people for « eminent services to chamber music ». As well as the Fourth Piano Sonata, in 1930 she had commissioned Tansman's Triptych for string orchestra (or string quartet). It was to her that Tansman dedicated his Serenade no. 3 for orchestra (1943).

[21] The first movement, « Andante cantabile » is written for wind instruments, percussion and piano, the second for string orchestra and string concertino quartet and the third for the full orchestra, the last one being for choir and orchestra.

[22] The programme works were the Symphonies no. 5, 6, 7, Deux Moments symphoniques, the Serenade no. 3, the Rhapsodie polonaise, the Triptyque, the Partita no. 2 for piano and chamber orchestra (1944) and the Suite for two pianos and orchestra.

[23] Igor Stravinsky by Alexander Tansman, Paris, Amiot-Dumont 1948.

[24] The two other compositions which Tansman considered the most successful of his career were his Concerto for orchestra (1954) and the lyrical fresco Sabbatai Zevi (1958).

[25] Franz André, Manuel Rosenthal, Vladimir Golschmann, Charles Brück, Stanislaw Wislocki, Igor Blazhkov, Maurice Le Roux, Eduard Flipse, Jean Fournet, Renard Czajkowski, Tadeusz Strugala and Antonio de Almeida.

[26] The main works performed were Stèle in memoriam Igor Stravinsky, Concerto no. 2 for piano and orchestra, the Ėlegie à la mémoire de Darius Milhaud and the Concerto for orchestra.

[27] The programme comprised Hommage à Erasme de Rotterdam, the Concertino for piano and orchestra, the Ėlegie à la mémoire de Darius Milhaud and the Concerto for orchestra.

[28] Quatre Danses polonaises, Concerto no. 2 for piano and orchestra, Quatre Mouvements pour orchestre, Rhapsodie polonaise, Concerto for cello and orchestra, 8 Mélodies japonaises, Quatuor à cordes no. 6, 11 Interludes for piano and Suite in modo polonico for guitar.

[29] The editors of Musica et Memoria express their grateful

thanks to Madame Mireille Zanuttini for permission to publish this biographical

note by Mr. Gérald Hugon. It may also be consulted in the collection Hommage

au compositeur Alexandre Tansman (1897-1986), published in 2000 by the

Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne, comprising 16 essays edited by

Pierre Guillot of the University of Paris IV-Sorbonne, grouped into four parts:

Biographie, Style, Analyse et Esthétique, Diffusion et réception de l'œuvre

(254 pages, ISSN: 1275-2622, ISBN: 2-84050-175-9, price 25 €). The publication

may be ordered from the Association des Amis d'Alexandre Tansman.

March 30, 2014 in the Médiathèque Alliance Baron Edmond de Rothschild

(with gracious permission by Mme Mireille Tansman Zanuttini) DR.

LIST OF WORKS